The Hawthorne Effect

Why would I urge you to spend extra money to “do it right” when we know from solid scientific research that not doing so will, nonetheless, often produce a quick, low-cost victory?

Let’s go all the way back to 1924 when a famous research experiment was undertaken at Hawthorne Works, a Western Electric Factory in Chicago. The factory commissioned a study to see if adjustments in workspace lighting might improve worker productivity. Light levels were increased, and productivity was measured. Sure enough, with a bit more light, productivity went up.

When workers were aware that their environment was being changed they saw this attention to their workspace as positive and caring and responded with increased productivity.

If the mere fact that any reasonable change usually delivers positive results, why bother spending more money to do it right? The answer is simple. When the implementation of changes stopped, the success quickly faded, and the adjustments produced only a temporary boost of productivity. The victory was temporary.

As it turns out, the scientists had discovered what is known as The Hawthorne Effect, an effect of expectation like the Placebo Effect or the Pygmalion Effect. Sure, you can score some quick points with a short-term productivity boost, but how should we sustain improved results in the long run? Experience teaches us that in acoustics “doing it right” is seldom a waste of money. What the Hawthorne factory needed was the objectively proper amount of light for a task. An adjustment providing too much or too little light might produce a temporary feeling of success, but in the long term, worker productivity is best served by objectively providing the “right” amount of light.

In the same fashion, acoustics works best when administered in the appropriate amount. While opinions vary a little bit, acoustical consultants/scientists almost always know what works best for a particular environment. Doing it right is in a large measure a matter of objective science. Lasting results allow the changes to be appreciated over time. Be careful not to pinch those pennies to the pound-foolish limit. The proper acoustics for workspaces is not a cost that needs to be justified, but a solid investment in productivity over the long term. Fortunately, good business managers recognize solid investments.

Glossary of Terms

Hawthorne Effect: For more about this topic: http://www.economist.com/node/12510632

Chuck Chiles, Director of Technology, Unika Vaev Acoustics

—

The Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne Effect, often defined as how people in a study act differently because they are being watched, is a type of reactivity. Reactivity is a phenomenon that happens when people know or suspect they are being observed and therefore modify their behavior; those modifications to behavior can cause positive or negative results.[1] The name of the effect comes from the interpretation of a series of experiments, often referred to as the Hawthorne studies or Hawthorne experiments, beginning in November 1924 at the Hawthorne Works industrial plant in Illinois. These initial experiments involved changes to the worker’s environment such as lighting, work hours, and even break times in order to measure any changes in productivity.[2][3][4]

Because the results of the Hawthorne studies have garnered various interpretations, reanalysis, and new findings over the years, The Hawthorne Effect no longer has a specific definition and has been defined both narrowly and broadly since the 1950s. Some newer analyses even conclude that The Hawthorne Effect does not exist at all or has been wrongly applied to results over the years. Wickström proposed that “in general, the term ‘Hawthorne effect’ should be avoided” [5] when evaluating the results of a study.

History

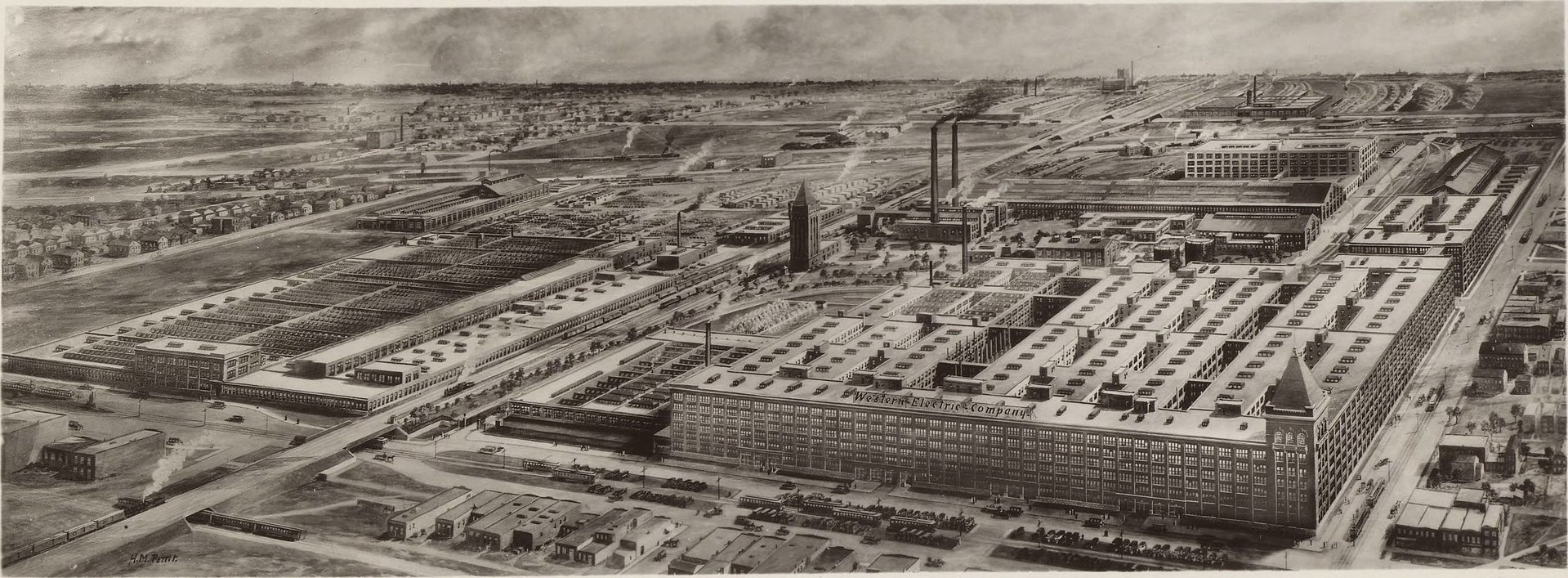

The Hawthorne Works was a Western Electric Company factory located in Cicero, Illinois. Western Electric manufactured telephones, cables, transmission equipment, and switching equipment, and was the sole supplier of telephone equipment for AT&T. The plant’s construction began in 1905 and covered more than 100 acres. It grew over the next few decades to include manufacturing and production factories, offices, laundering facilities, a hospital, a fire brigade, and even a greenhouse.[6] The Hawthorne location housed the most cutting-edge industrial technology. This particular factory also employed more than 40,000 workers at one point during the studies, largely consisting of immigrants from 60 nationalities.[7] Employees carried out extremely precise and measured tasks in specialized, compartmentalized units.

After years of media exposure of the poor working conditions found in many factories in the US, people and companies began taking an interest in the welfare of the individual worker. Companies started offering a variety of benefits to improve employee relations and the introduction of safety equipment to reduce injuries. This shift in thinking and treatment prompted Western Electric, as a large employer with a substantial output, to look for a better understanding of employees. Behavioral, medical, and social studies became an interest in order to increase productivity and satisfaction.[6][7]

Because the Hawthorne Works utilized the scientific management,[4] a theory described by Frederick Winslow Taylor in his book The Principles of Scientific Management, in order to control production departments and output, such as with equipment that required hundreds of separate operations for assembly and inspection, this plant was ideal for a study concerning productivity.

With such an enormous plant and body of employees at Hawthorne Works, Western Electric needed support from other organizations in order to carry out a study. Partnered with the National Research Council (NRC), the Rockefeller Foundation, and Harvard Business School,[6] they conducted a series of behavioral experiments from 1924-1933. Western Electric sent two engineers, George Pennock and Clarence Stoll, to oversee the study with the support of the NRC’s Committee on Industrial Lighting.[7] However, it is important to note this committee had a vested interest in the use of artificial light in the workplace.[8]

Electric companies had been competing with gas companies over the use of lighting fixtures since about 1895, but the more energy-efficient electrical lighting used less power. In order to get customers to use more power (and thus generate more revenue for the electric companies), the industry started testing “more light = more productivity” to establish a higher need. As company managers were not convinced by previous campaigns, the NRC formed the Committee on Industrial Lighting (CIL). The CIL included many respected and well-known engineers, and Thomas Edison was appointed as the honorary chairman to add credibility to the testing.[8] Over the years, the studies at Hawthorne recorded various data such as hourly performance charts as well as interviews with thousands of employees.

The Illumination Studies, 1924-1927

Under the direction of the National Research Council, the Illumination Studies involved three departments. It is important to note that findings from Levitt & List show that, for the first two parts of the tests, natural light sources in the test rooms were not eliminated and therefore varied throughout the day.[8] Also, because the test rooms were naturally and artificially illuminated and natural lighting was sometimes sufficient due to seasonal changes, no data was collected from April 1925 through February 1926 and April 1926 through September 1926. Tests concluded in April 1927.[8]

In the first test, three experimental groups had artificial lighting levels increased incrementally. As lighting was increased, researchers noted that productivity also increased. However, as the researchers continued with the experiment and began to decrease the lighting, productivity levels continued to increase. Lighting levels ranged from 4-foot candles of artificial lighting, which was the original factory level and set as a baseline, up to 36-foot candles. But because there was no control group, the results could not be accurately interpreted. Researchers decided a new test design was needed.

The second part of the experiment ongoing from February 1926 through April 1926 studied two groups, a control and an experimental group. The control group worked under constant lighting levels, while the experimental group worked under increasing lighting levels. Again, the artificial lighting levels for the experimental group ranged from 4-foot candles to 36-foot candles and no attempts to control natural light were made. Researchers again found an increase in output for both groups.

The third part began around September 1926 and was designed similarly to the second part; however, the researchers manipulated the natural lighting levels by blacking out all windows in the rooms.[8] The light stayed at constant levels for the control group but was continually decreased for the experimental group. The experimental group started with 11.5-foot candles of artificial light. The level in the experimental group was incrementally lowered, and both groups saw increases in production each time until the experimental group reached as low as 1.4-foot candles for one day. The levels were returned to 11-foot candles the next day. The Illumination Studies concluded shortly after returning the levels to 11-foot candles, near the end of April 1927. Although some reviews have noted increases in all three groups, Levitt & List did not find recorded data for the output of the control group during the third part;[9] output was recorded only for the experimental group. This lack of data makes estimates for increases difficult or impossible.

Another important note is that all lighting changes were scheduled for Mondays so employees in charge of lighting alterations would be able to make changes while the factory was closed on Sunday. With each new lighting level, researchers informed the experimental group workers of the change.[9]

Data compiled by Levitt & List roughly show a 10% per year increase in productivity in the groups of the three departments following the start of the Illumination Studies, regardless of whether they were part of the control or the experiment. When the tests paused in April 1925, productivity decreased slightly but remained above the baseline set before the tests began. The same changes occurred with each start and stop. Their estimations based on annual reports from the 1920s suggest that the company overall only had a 1.4% per year increase in productivity from 1924-27.

After this first experiment yielded no real results or conclusions that supported brighter lighting equaled better productivity, the National Research Council pulled out of the study. However, Western Electric decided to continue with the efforts. The researchers still involved determined other factors were affecting worker output and further investigation was required to understand what was occurring.

The Relay Assembly Test Room (1 and 2), 1927-1933

Between 1927 and 1929, the workforce at Hawthorne almost doubled — surging from 21,929 employees to 40,272.[1] George Pennock, then promoted to technical superintendent at Western Electric, brought in consultants to help continue the studies. The Relay Assembly Test Room (RATR) studies spanned from May 10, 1927, until May 4, 1933, and involved 24 periods of testing.[8] Planning began as early as April 25, 1927, a week before the Illumination Studies concluded, and tests were only supposed to last for a short period in 1927.[10] Since the findings of the Illumination Studies were inconclusive, researchers wanted to determine other variables that might affect productivity.

The relay assembly department was tasked with making electromagnetic switches. These switches are what allowed telephones to make connections as each number was dialed. Repetitive assembly was required, involving items such as pins, coils, screws, and other small components. Western Electric considered the speed of individual workers to set the overall levels for productivity, so accounting for multiple factors was crucial to the bottom line. How much time a worker spent actually performing a task versus breaks and the length of the workday became of particular interest throughout the experiments. This set of experiments was established to study the employees’ performance when in a controlled environment; both a supervisor and a researcher were present.[11]

They picked two female workers, who were then instructed to choose four more women. The six employees were then moved to a separate room. Five of the women worked on assembly, and the sixth kept them supplied with parts.[7] Overall, they worked together assembling relays for five years.

The women, referred to as ‘girls’ by the investigators, worked in a row while dropping each completed relay down a chute where it was recorded with a hole punched into tape. Across from the line of workers sat a supervisor with his assistants. According to Gale, “Pennock and Stoll were engineers, and treated the row of women like an engine in its test bed, tweaking the conditions to achieve maximum output.” While output was measured by a chute that counted completed relays, the in-room supervisor discussed changes with the group, as well as took and implemented suggestions. The supervisor took on a friendly role, allowing much more freedom than was previously allowed in earlier managerial methodologies.

Researchers tested modifications to the work environment and structure. Pay was varied based on group versus individual production. After a discussion on the best length of time, the researchers provided two 5-minute breaks a day; then they tested two 10-minute breaks, which was reported to not be their preference; and finally, they tried six 5-minute breaks per day. The final variation was disliked by all six of the women, who reduced output during this change. The researchers even tested changes like providing snacks during breaks and shortening the work day.[3] When the work day was shortened by 30 minutes, output went up. Shortening the work day length further increased the output per hour but reduced the overall daily output. Finally, they tested returning to the original work day length, and output peaked. Gale notes that Pennock was puzzled when nearly any change seemed to continually increase productivity, even when they returned to the original work environment and structure for 3 months in 1928. Output went from a baseline of 2400 to 2900 to 3000 relays per week.[7] These changes, at least with early interpretations, led to J.R.P. French to coin the term “Hawthorne effect” in his influential methodology textbook Experiments in field settings (published in 1953) to describe what happened.

The results were too confounding for the investigators involved, so they decided to turn to academic consultants. Western Electric connected with Harvard Business School and brought in Elton Mayo, well known today for his involvement with the Hawthorne experiments. Mayo held the title of Associate Professor of Industrial Research at the time. T.K. Stevenson, the personnel director for Western Electric, sent a copy of the relay test reports to Mayo and suggested he visit Hawthorne to see the studies for himself. Clair E. Turner, a professor of biology and public health from MIT, also joined the researchers for the Hawthorne experiments at the request of Pennock. For the studies at Hawthorne, Turner created a device to be used on the wrist; this instrument applied pressure to the skin that created a line. The line would disappear after a certain amount of time, allowing the researchers to determine vascular skin reactions — something they believed would indicate fatigue. However, the readings varied widely regardless of improvements to the device, and the subsequent data provided little indication as to actual levels of fatigue.14 Roethlisberger

According to Gillespie, Turner and Mayo were not present at the facility at the same time at any point during 15 documented visits in 1928 and 1929, and this was most likely deliberate. Because Turner and Mayo could not and did not collaborate on the tests, the Hawthorne managers were left to interpret the results at that point, independent of the two consultants.

After receiving a second progress report from Stevenson, Mayo traveled to Hawthorne. Mayo’s initial visit took place in April 1928 where he measured the participants’ blood pressure throughout the day and then left.[7]

This may seem odd, considering the objectives of the study; however, Mayo was already making a name for himself regarding his new theories regarding industry and people. In earlier consultations, Mayo helped a Philadelphia textile mill with high worker turnover rates. He introduced breaks, or “rest pauses,” to the workers’ schedules. He believed that fatigue and the monotony of the tasks caused “pessimistic reveries.” He determined that the simply allowance of break eliminated this problem.[12] Due to his research, he believed blood pressure measurements could signify levels of fatigue, hence the blood pressure readings at Hawthorne. Mayo was particularly interested in the studies at Hawthorne since they involved experimenting with breaks.[1] However, the records eventually indicated that the increase in productivity was not due to a decrease in fatigue, so at this point, other studies began to form; however, experiments with the Relay Assembly Room Test continued for several more years.

Homer Hibarger and Donald Chipman, both supervisors for Western Electric, observed, reviewed, and maintained data concerning the variations to the work conditions. With the changes, the output levels continued to increase in almost all instances. This contributed further to the earliest interpretations referring to the occurrence as The Hawthorne Effect. Mayo concluded that the individuals in the RATR study became a team; this conclusion contributed to Mayo and Roethlisberger’s thoughts on attitude, supervision styles, and how important relationships in a group all were to productivity and job satisfaction.[6] According to French, all of these factors led to special treatment of the women in the study, and that therefore spurred the increases in productivity, creating The Hawthorne Effect. [13]

A subsequent RATR group was later formed during the experiments to test changes in wage incentive and breaks, starting on November 26, 1928. The pay was originally based on individual instead of group output, so a group output rate was in place for nine weeks until January 26, 1929; however, no rest periods or breaks were given. The output increased while the group rate was in effect. Contrary to previous findings that any change was the factor in increased productivity, the test group showed a decline in output once the change in wage incentive concluded. Returning to the old pay scale resulted in a decrease instead of an increase. Roethlisberger concluded later that pay was, in fact, a significant factor.[14]

By June 1929, the Relay Assembly Test Room had an output of 30% higher than the baseline from May 1927.

The Mica Splitting Test Room, 1928-1930

These tests were designed to mimic the RATR experiments and to establish whether the results of that test would follow; researchers decided to introduce similar changes in working conditions but no changes in pay incentive.[14] One objective was to extend the test periods of this experiment since the RATR tests had proven to be too short. Another objective was to measure the effects of overtime; production schedules were strained, causing departments to require overtime hours in order to meet demand, so study on the effects of additional work hours could prove beneficial to the company.

Mica splitting involved very delicate, very precise tasks that required a close attention to detail. Most workers performing this task would become noticeably better at it over the first several years on the job. According to Roethlisberger, this was one of the more desirable jobs at the plant because of the relative physical ease combined with high pay. Starting in August 1928 and continuing for eight weeks, the experiment measured the output of five experienced, random employees. None were made aware of the experiment at that point, and all measurements for output were taken without notice. However, when asked to participate in the study, only two of the five women agreed.[14] These two women were asked to select three other women to join them. Researchers then met with the group to discuss details of the study.

On October 22, 1928, the operators were moved to a well-lit, private room. For the first five weeks, no changes were made to the work conditions. After, researchers included two ten-minute breaks, one at 9:30 AM and one at 2:30 PM, for the remainder of the experiment. Because the RATR experiments had concluded that there was an increase in output independent of the number and length of breaks, no other changes were instituted for breaks. At this time, the workers were experiencing overtime conditions consisting of a 55.5-hour work week. When work hours returned to a normal 48-hour work week on June 15, 1929, the breaks remained until a nearly a year later on May 19, 1930, when, due to the economic depression, the work week was shortened to 40 hours. Nearly four months later, the study was abandoned because of the worsening economy and was officially terminated on September 13, 1930.[14]

While both the RATR and Mica test rooms experienced increases in output in the first year with changes to the conditions, the Mica room experienced a decrease in output the second year. This was likely due to economic conditions. Also, no overall improvements in attendance were observed in the Mica group as they were in the RATR group. Unlike the RATR group, the Mica group did not socialize outside of work hours and did not converse about personal topics outside each worker’s social life. The workers in the Mica group did not seem to have a cohesive, team-effort attitude as far as output levels and remained focused on individual efforts. According to Roethlisberger, multiple shortcomings in the design of the Mica group study resulted in it falling short of experimental conditions. This may be one of the reasons the Mica group study is rarely analyzed or referenced in other texts.

The Interviewing Program, 1928-30

Assisting Mayo during his time working with the Hawthorne experiments was his research assistant, Fritz Roethlisberger, who studied philosophy at Harvard. Known as an expert listener because of his work as a psychological counselor at Harvard, Roethlisberger, along with Mayo, began extensive interviews with Hawthorne employees. Sheldrake notes the plant-wide interviews began in September 1928 and continued until 1930. According to Anteby in the essay A New Vision, interviews were formal in structure and averaged half an hour initially but increased to 90 minutes and up to two hours in length. While the researchers hoped to find details that might play a part in attitudes toward work and supervisors, a shift occurred that led to workers opening up about intimate details, more so than expected. The interviews became an emotional release. Over the two year period, Mayo and Roethlisberger coordinated more than 21,000 interviews. Anteby notes, “Both workers’ and supervisors’ comments would aid in the development of personnel policies and supervisory training, including the subsequent implementation of a routine counseling program for employees.”[6]

The Bank Wiring Observation Room, 1931-32

In 1931 Mayo and Turner began an experiment, assisted by W. Lloyd Warner who was an industrial anthropologist at Harvard, that they thought would replicate the Relay Assembly Room Test, but they focused the study on men instead.[4] This experiment focused more on the social aspect of the informal groups formed by the participants and included observations of how pay affected productivity. It began with 14 men who performed three different jobs. The test group work included wiring, soldering, inspection of banks of telephone switchgear. Separated from the rest of the department, the men worked with the normal supervisors and a researcher who acted solely as an observer; this is in contrast to a warm, friendly RATR supervisor who promoted freedom and intimacy in the informal social group setting.

Researchers observed that, unlike with the RATR group, productivity decreased. The reason behind the decrease involved a fear the men held — a loss of income. They were concerned that the company would lower the base rate if they worked faster or better than normal, and therefore began establishing cliques to enforce rules and standards for output, as well as behavior. The workers started to respond with unified answers, regardless of the truth. Whereas other groups responded positively to being observed and the changes of the study, these employees responded with defensive behavior. The group had determined a rate of output that was lower than the manager’s standard, what Sheldrake refers to as a classic example of calculated output restriction. Any worker found trying to improve upon this lower output was reprimanded by his fellow workers, sometimes with verbal taunts or even physical blows.[4] Some definitions of The Hawthorne Effect could be applied to the results of this study, where the subjects of the study changed their behavior because of the extra attention, though most do not apply The Hawthorne Effect here.

Interpretation & Criticism

The earliest interpretations suggested that any change led to increased productivity, but too many factors confounded the results. In the 1970s, behavioral psychologist Henry McIlvaine Parsons reviewed accounts of the research in Science magazine, reporting significant issues with the experiments,[15] and saying he would define The Hawthorne Effect as “the confounding that occurs if experimenters fail to realize how the consequences of subjects’ performance affect what subjects do.” A 2014 analysis of 19 studies led by Jim McCambridge involving or referencing The Hawthorne Effect concluded that “…the effect, if it exists, is highly contingent on task and context.”[16] McCambridge notes, “Consequences of research participation for behaviors being investigated do exist,” but that the methodologies need to be updated for studies.

Steven D. Levitt and John A. List published a new analysis in 2011 concerning The Hawthorne Effect and including new details from previously lost data from the Hawthorne studies. When examining the data, they found “more subtle manifestations” of The Hawthorne Effect and proposed a new method for determining if The Hawthorne Effects are present in a study. The researchers go on to say, “Our analysis of the newly found data reveals little evidence in favor of a Hawthorne effect as commonly described, i.e., productivity rising whenever light is manipulated. A naïve reading of the raw data does produce such a pattern, however.” Levitt also points out that it is problematic to have such a broad definition for The Hawthorne Effect, as that poses difficulties in testing for such an effect.[9]

In an article published by the New York Times in 1998, Dr. Richard Nisbett from the University of Michigan called The Hawthorne Effect “a glorified anecdote,” in part for the small sample size of the study.[17]

John Adair suggests in his 1984 article “The Hawthorne Effect: A Reconsideration of the Methodological Artifact” that a closer look at the definition of the effect is required. Numerous studies have failed to replicate the conditions of the Hawthorne experiments, and definitions used in secondary publications vary widely. According to Adair, The Hawthorne Effect should more of a priority for researchers.[18]

Wickström notes in an abstract published in the Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health that “in social research, there is much critical literature indicating that, in general, the term ‘Hawthorne effect’ should be avoided.” The author goes on to suggest researchers should be more specific about the variables that may have guided the results of the study but were not monitored, along with how those variables could have affected the observed results.[5]

Overall, many agree that the term has often been misapplied in general and overused. Regardless, the term “The Hawthorne Effect” persists both in educational and professional texts in several fields such as business, psychology, and economics.

—

[1] Gillespie, R. (1991). Manufacturing Knowledge: A History of the Hawthorne Experiments. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=DN6kyW8Ca44C

[2] Obrenović, Ž. (2014). The Hawthorne studies and their relevance to HCI research. Interactions, 21(6), 46-51. Retrieved from http://interactions.acm.org/archive/view/november-december-2014/the-hawthorne-studies-and-their-relevance-to-hci-research.

[3] Khurana, A. (2009). Scientific Management: A Management Idea to Reach a Mass Audience. Global India Publications. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=MaOcIx7h91EC

[4] Sheldrake, J. (2003). Management Theory. Cengage Learning EMEA. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=59Qi-X9PEgoC

[5] Wickström, G., & Bendix, T. (2000). The “Hawthorne effect”–what did the original Hawthorne studies actually show? Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 26(4), 363-367. Retrieved from http://www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=555

[6] Anteby, M., & Khurana, R. (n.d.). A New Vision. Retrieved from https://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/hawthorne/

[7] Gale, E.A.M. (2004). The Hawthorne studies—a fable for our times? QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 97(7), 439–449. Retrieved https://academic.oup.com/qjmed/article/97/7/439/1605689

[8] Samson, D., & Daft, R.L., Donnet, T. (2017). Management. Cengage Learning Australia. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=6ENMDwAAQBAJ

[9] Levitt, S. D., & List, J.A. (2011). Was There Really a Hawthorne Effect at the Hawthorne Plant? An Analysis of the Original Illumination Experiments. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, American Economic Association, 3(1), 224-38. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w15016

[10] Homans, G.C., Hamblin, R.L., & Kunkel, J.H. (1977). Behavioral Theory in Sociology: Essays in Honor of George C. Homans. Transaction Publishers. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=bcBPEvR7yrcC

[11] Corsini, R.J., Craighead, W.E., Nemeroff, C.B., & Nemeroff, L.M.M.P.C.C.B. (2001). The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology and Behavioral Science. John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=ayqEGljUVr8C

[12] Ionescu, G.G., & Negrusa, A.L. (2013). Elton Mayo, an Enthusiastical Managerial Philosopher. Revista de Management Comparat International 14(5), 671. Retrieved from https://unikavaev.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Marshfield-Collection-triple-fold-card-002.pdf

[13] French, J.R.P. (1953) Experiments in field settings. Research Methods in the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

[14] Roethlisberger, F. J., Dickson, W.J., & Thompson, K., ed. (2003). Volume 5 of The Early Sociology of Management and Organizations: Management and the Worker. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=z5BZ72cwZlYC

[15] Parsons, H.M. (1974, Mar 08). What Happened at Hawthorne? Science, 183(4128), 922-932. Retrieved from http://science.sciencemag.org/content/183/4128/922

[16] McCambridge, J., Witton, J., & Elbourne, D. R. (2014). Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(3), 267–277. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3969247/

[17] Kolata, G. (1998). Scientific Myths That Are Too Good to Die. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/review/120698science-myths-review.html

[18] Adair, J.G. (1984). The Hawthorne Effect-a reconsideration of the methodological artifact. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(2), 334–345.